As Political as it Gets: Service Design & Social Innovation

The following is a transcript of a talk I gave at Service Design Now in Melbourne, Australia, May 2018

I’m gonna get political, Because I want you to get political, Because the work we do is political.

I’m Dr Reuben Stanton. I’m the design director and a co-founder of Paper Giant. Paper Giant is a strategic design consultancy. Our purpose is to make positive change through design.

We’re passionate about working with, and designing for, communities of all kinds. We work in the public and private sector, at all levels of government, and in health, education, and social justice.

Today, I’m going to talk about ‘social innovation.’ I want to use this opportunity, with the this amazing community of practitioners, to interrogate what it means for a design consultancy like ours to do that kind of work.

Let’s start with a definition:

‘Social innovation’, simply, is about developing new and innovative responses to existing social problems.

So… what kinds of problems are we dealing with right now? We’re dealing with a world that is suffering — from a series of interconnected and complex problems at many different scales.

We’ve made loads of progress technologically, socially and economically in the last 200 years. But for some reason, we’re faced with:

- Rising levels of inequality, loneliness, depression, unemployment

- Ecological disaster

- Failure of political systems, and the loss of trust around the world in the media, democracy and political institutions…

To me, this looks like evidence — that our ‘business as usual’ approach to things isn’t working.

Something about our system just doesn’t seem right to me

We want to innovate because we actually want to build a better society for everyone. We want to look for new approaches to problem solving — ones that make things better, not worse

And I can hear you asking — what does better mean? For us: it means more just, more fair, more equal, more sustainable futures

- More just: better access to justice, for all of society

- More fair: equitable access to resources, for all of society

- More equal: better access to opportunity, for all of society

- More sustainable: better use of limited resources, and more stable and resilient solutions, across all of society

Sounds great, right? And Service design is interesting to me here, because what Service Design tries to do is map systems, and help people make decisions about systemic change.

Reasonable goals!

How might we drive decisions that lead to more just, fair, equal, sustainable futures?

Lately we been working a lot with the fines system.

Here’s a story: A 50 year old man, let’s call him Nick, a client of a legal and financial counselling service we were working with, had so many infringements that he would lose his house if he paid them. He would also lose his house if he ended up in Jail because he didn’t pay them. This man was recovering from a serious drug addiction — he’d got himself out of that situation, but the risk was that he could pay his fines, be made homeless, and, in his words, would ‘end up dead’ because he would just go back to abusing drugs again. This is his file:

A financial counsellor we spoke to managed to get him onto a payment plan, got arranged for him to take on some borders to pay the mortgage. She counselled him to find work to keep going till he was 55 so he could access his super, and arranged a special circumstances provision on account of his drug addiction. As you can imagine this took a long time to sort out — multiple consults, digging around for documentation and medical records, administration.

People in rehab often have serious financial difficulty as a result of their addiction, and have sometimes collected ten thousand dollars or more in fines. Extreme cases, like Nick’s, can be eighty thousand dollars. People get to the point where they are going to lose their house or go to jail.

This is a social problem. The government is not getting generating revenue from these people — it often costs more to recover the fines than the value of them. It causes undue stress on the community and pain to real people in need.

Let’s do some social innovation!

A common assumption in social support spaces — is that we, as a society, should always direct resources towards those most in need. Makes sense.

But looking at this problem with a systemic lens — the community legal sector is almost entirely funded by the government — through operational funding, and grant funding for specific projects. It’s taxpayer money. A lot of this money is actually ‘wasted’ — dealing, not with clients in dire need like Nick, but with a ‘middle’ cohort of people that really should not be any pressure on the sector at all.

These are people who have what we call ‘high legal capability’ — they could help themselves if they had the means and the information to do so. Those means are hard to find, and so they call Legal Aid or a community legal centre and take up valuable time. A lot of this pressure is fines related. We’re talking 1 or 2 parking fines or a public transport fine, not 80 thousand dollars like Nick.

The reason dealing with clients like Nick is is a problem, is that there is not enough time to work with them, not that the system for helping them fails — Remember — Nick’s story was a success story!

Design thinking helps us ask questions like: ‘how might we take pressure off the system in the first place so we can help people like Nick better?’ It meant designing and building a resource specifically targeted at the cohort that are not the ‘most in need’, but instead the most capable.

We recently worked on a project called FineFixer — a digital tool, a process, and a free service — to help those with the capability deal with fines in a timely manner, and those without the capability to be directed to the correct help the first time around. There is a great design story behind this particular intervention too that involves working with concepts generated by students, a small community legal centre, and some clever uses of resources and technology.

But I’m not going to go into that today. I actually want to talk about something else — yes, the outcome was a success, it worked, it’s working — but what I want to interrogate is a structural issue with how projects like this happen.

I want to talk about policy.

“Policy” is how organisations arrange their resources to express operational and strategic goals.

The fines system? It’s government policy.

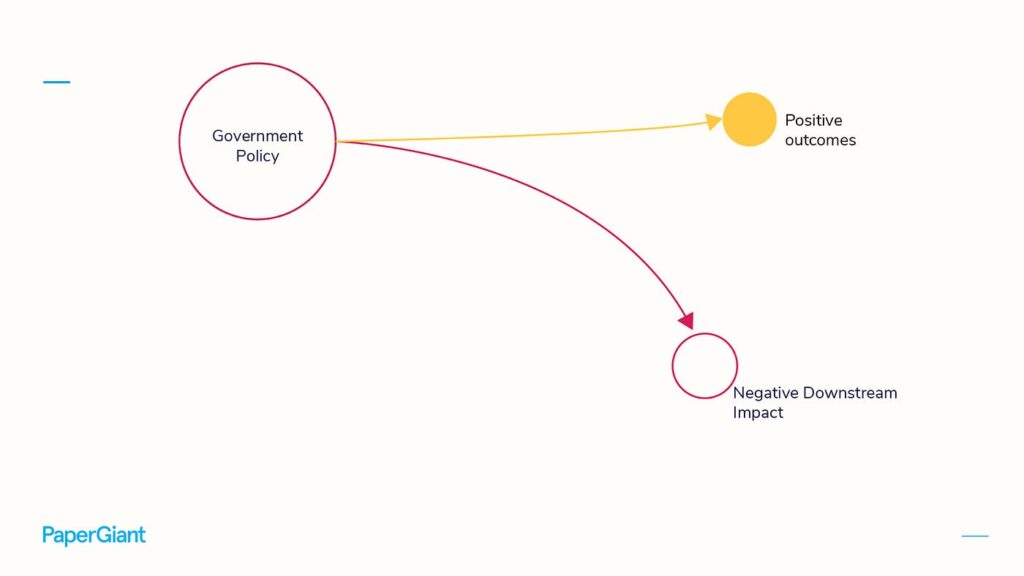

The fines system was created with a strategic goal: to deal efficiently with minor criminal offending, where the offence isn’t that serious, so it’s not worth getting a court involved. That works for people who can pay — it’s a minor inconvenience, works as a deterrent — this should be most people if the fines are proportionate.

But guess what? In some cases, for the most poor, the most vulnerable, the most in need? They’re not proportionate.

For people who can’t pay due to totally reasonable circumstances — say, you get a speeding fine because you are fleeing an act of family violence, or you get multiple public nuisance fines because you are homeless — the purpose of the fines scheme is lost. Instead people are forced through a complex legal process that is more cumbersome than if the fines system didn’t exist in the first place.

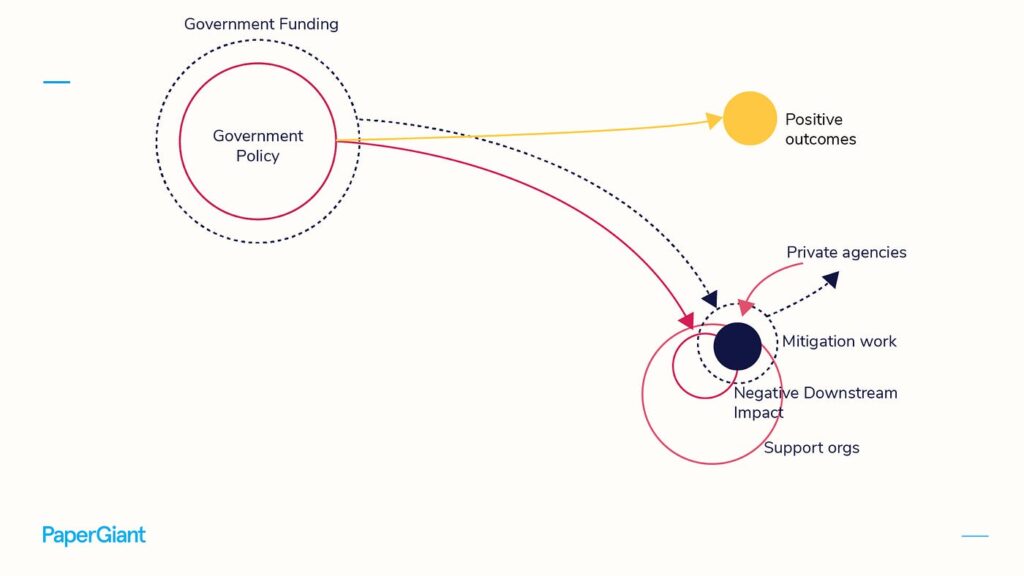

This is negative downstream impact on the most vulnerable.

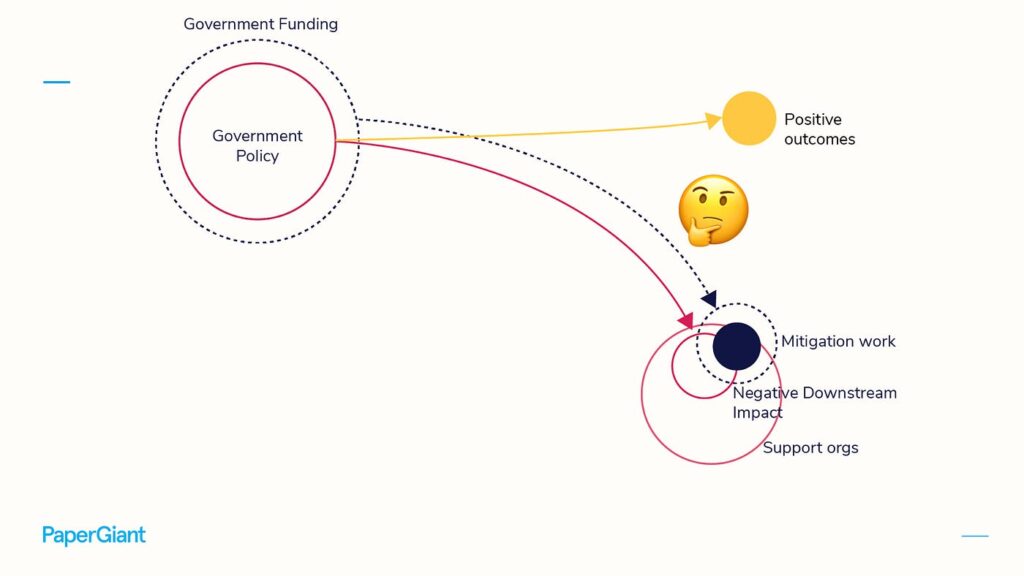

Now — there are support organisations working in this space to help mitigate this impact — this is awesome, they do awesome work— community legal centres, legal aid, health and social work organisations. They assist people in need through the system.

They do what I like to call “mitigation work” around this policy failure. But how are most of these orgs funded? With government money.

Can anyone see a problem with this system?

Now — social innovation often happens in this space. A private agency (us) is brought in to help with this mitigation work and make it more efficient, to scale it, to use design to make it more effective.

Why us? Most support orgs have capacity to help their clients, but they don’t have the design capacity to do the innovation work — to help them solve problems of service capacity, of service delivery. Service design! Strategic design! We come in, we can help out. For our efforts we take some of that government money.

Hmmmmm…

Does this look like a great use of resources to you? Does it look just, fair, equal, sustainable?

Government makes problem. Government collects taxes. Government spends taxes to solve problem. Private enterprise takes taxpayer money to help solve the problem. Problem continues because government policy remains the same.

Sometimes this is what social innovation work feels like. Does your job ever feel like this?

Now… we might be getting good results addressing the problem at hand. Design is really good at that — working collaboratively, with the affected community and those that can help, establishing ways to manage, support, and change outcomes. That’s not good enough. It’s treating symptoms not causes.

So… what else can we do?

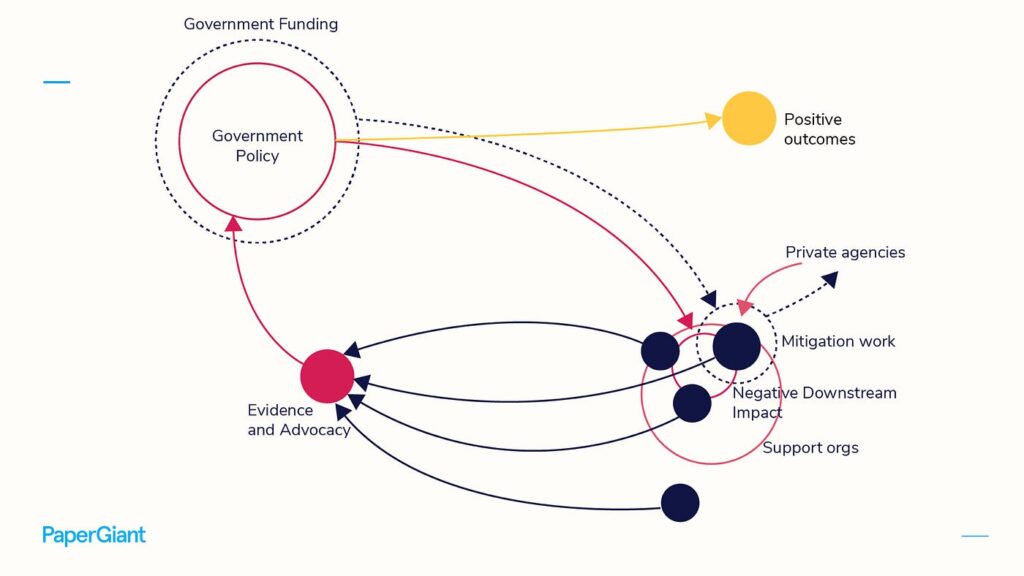

One of the things we try to do is collect evidence. Evidence that might is useful for solving the problem at hand, but that also points to opportunities to change the root cause. We work to build that evidence, and explicitly advocate for change.

A bit better?

As as a small, private entity, we are not usually in a position to do that advocacy ourselves. We have no access to the halls of power. But often our clients — the support orgs we work with — they do!

It’s pretty hard for us to advocate for a change in legal framework that makes up the fines system in Victoria. But Victoria Legal Aid? They can totally do that. And we can help them, through our projects, improve that advocacy.

And what’s super important here is a strategy. We’re doing multiple projects in this space. For example, we’re currently working on another project explicitly about working in rehab settings, to improve outcomes for the most downtrodden, in one of the most oppressive parts of the system. We’re not ignoring the most in need, we’re designing for that too!

Better?

But, perhaps more importantly, we’re also collecting more evidence. More data. More stories. Data which demonstrate how and where the system breaks down. We don’t have the power, clout or networks to advocate for change, but our work can agitate and can collect evidence for others with that power.

But ultimately, what would solve the problem in the best way?

We need to change the policy.

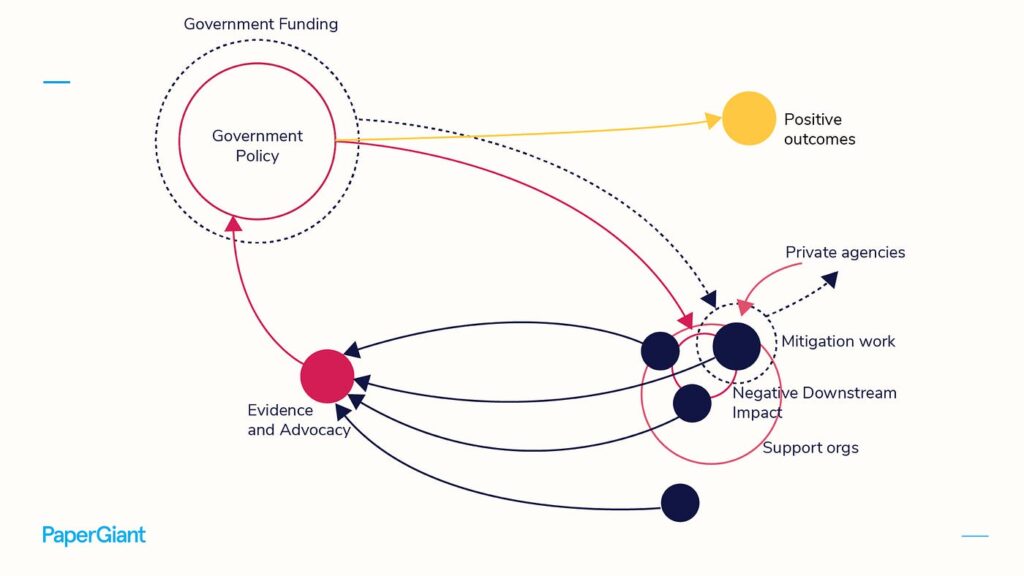

Because this! This is the model we want!

Often, really often, Service Design is about mitigating failures caused by an organisation at a systemic level. This approach? It’s not just for ‘social innovation’. Are you working in customer experience, fixing problems with the customer journey, when the real problem is that your customers don’t need the product? Or the real problem is that your organisations KPIs are wrong and so don’t reflect actual success? What are you doing to enable systemic change while you mitigate those failures?

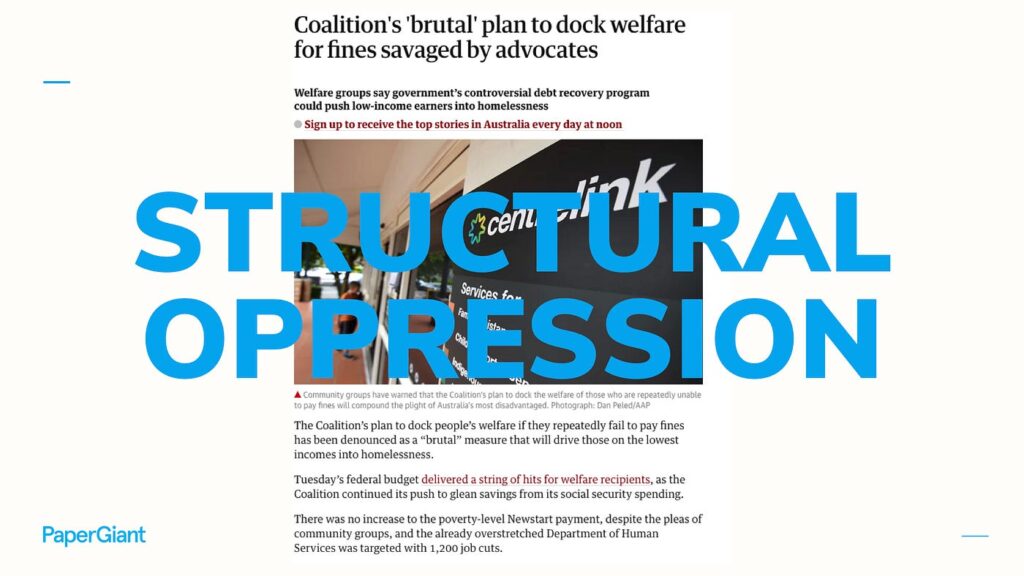

Now, sadly, sometimes policy, the expression of strategic goals, is oppressive in nature. It’s designed to take a punitive approach, to marginalise, to ignore, to punish.

Sometimes the problem is ideology

Sometimes this is just because governments have the wrong KPIs. The structural goals are wrong. Just sticking with the example of fines — some councils right here in Melbourne have revenue targets based on fine enforcement. Can anyone see an issue with this? What kind of enforcement regime might this encourage? Do you think this might lead to a fair, just, equal or sustainable system?

Sometimes ideology will never allow for systemic change, and we no option but to work with mitigation strategies, until such time as we change the government.

This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t do this work! But the work we do as designers in a “social innovation” space must be aimed at more than solving symptomatic issues in a sick system.

So — if you work in government or organisations ? Please, please — work every day to make better systems! Evaluate your downstream impact. Work with all your might to change your policy when you can see that it’s not working.

Don’t get me wrong, I love solving problems for people. I do it all day. But I hate these social problems. I love my job. But I don’t want to live in a society where my job has to exist. I’m sick of being the guy with the mop and the bucket, I want to fix the leaky roof.

And if you work for a design agency or team? Get political! Please, solve the problem in front of you, solve with and for your communities! Keep doing that! But always, always work to learn about and change the systemic problems, and design ways to help others advocate, and to empower others to make positive change. Do both things. If you can’t make the change that is necessary, look for the people that can, and help them do it.

And as a private citizen? Get political! Advocate for, vote for, and elect representatives that have — policies and ideologies that are genuinely, actively, working towards more just, more fair, more equal, and more sustainable futures.

That’s it from me, thanks very much for having me here, thanks very much for listening.