Design Thinking for Social Innovation

The following is a transcript of a keynote presentation that I gave at the Business Improvement and Innovation in Government Regional Innovation Festival, in Maroochydore Australia on March 16 2018.

I’d like to first acknowledge the traditional owners of the land on which we meet today, and pay my respects to elders past, present, and future.

My name’s Reuben Stanton.

I’m designer, a researcher, and a recovering academic – I rarely get to call myself ‘Dr’ these days – so I’ll just leave it up there for a second for nostalgic reasons.

I’ve spent pretty much my entire working life so far in design. I started my career as a graphic and web designer in the late 90s, I worked as a software and web developer for about 10 years – but I was always more interested in how people used (or didn’t use) the things I was asked to make. I was more interested in the contexts that our digital products and services fit within than the ‘designed things’ themselves.

That interest led me first to a PhD in interaction design, an interest in systems thinking, organisational politics, and later, to found a design consultancy that looks across products, services, systems, infrastructure and policy.

The consultancy is Paper Giant.

We’re a research led design consultancy – based in Melbourne – we help organisations, governments, not for profits understand and solve complex problems.

We work across the spectrum of design projects – from discovery and problem space research, right through to service and product delivery, implementation and evaluation.

Our whole team is passionate about social innovation, and we do a lot of work with governments at all levels to help deliver better government services, build design capability and leadership in government, evaluate policy, and rethink what it means to do good work for communities.

I’m been asked today to talk to you all about “Design Thinking.”

I’m sure some of you are already well versed in the concept. Some of you may have heard the term about and wondered what all the fuss was about. Some of you may be new to it. I hope I have something for all you today.

But before I get into that, I want to talk briefly about social innovation, then I’ll talk about Design thinking and what it means, then I’ll go into some case studies – to make it a bit less abstract and connect it to the ‘real world’

To start – Social Innovation

‘Social innovation’, at its simplest definition, is about developing new and innovative answers to existing social problems.

What kinds of problems are we dealing with right now? What about the future?

Governments – all organisations – are dealing with a world that is suffering from a series of interconnected and complex problems at many different scales.

We’ve made loads of progress technologically, socially and economically in the last 200 years.

But somehow, we’re facing rising levels of inequality, chronic diseases, loneliness, and unemployment.

We’re facing the prospect of frequent natural disasters and widespread water and resource shortages.

And, to be honest, we’re experiencing failure of political systems and the loss of trust around the world in democracy and political institutions…

So why innovate?

There is ample evidence that our ‘business as usual’ approach to things simply isn’t working

Not to get too utopian on you this early in the morning, but if we’re talking about social innovation, we want to innovate because we actually want to build a better society for everyone.

Obvious question: what does better mean?

For us: it means more just, more fair, more equal, more sustainable

- More just: better access to justice, for all of society

- More fair: equitable access to resources, for all of society

- More equal: better access to opportunity, for all of society

- More sustainable: better use of limited resources, and more stable and resilient solutions, across all of society

And as workers in government, in not-for-profits, or in the private sector, you want to be able to come to work and say, ‘how can we make the world better, everyday?’

Social innovation looks to develop innovative answers that deliver on this promise.

So – what’s Design Thinking got to do with any of this? – what is it? What is it good for?

Can I just get a quick show of hands – how many of you here have ‘designer’ in your job title? What about ‘service designer?’ What about ‘researcher’?

I’m also gonna just run through some jargon: put your hand up, and leave it up, if you’ve heard any of these terms: Agile. Wagile. UX. CX. Service Design. Stand-up. Scrum. Product Roadmap. Backlog.

Ok, not leave your hand up if you feel like you understand those terms.

This might be a bit old hat for some of you. And that’s fine – reinforcement in learning is always good.

And just so everyone else feels comfortable, I’m not going to use any of that jargon in the rest of my talk.

Design thinking is a process by which we can discover opportunities, define solutions, develop and deliver value.

There are actually a whole lot of different ways to map this process – many different models.

Examples of ways this gets mapped include:

- the double diamond – originally from the british design council, but spread far and wide – if anyone has seen a model of ‘design thinking’ this is most likely the one that you’ve seen

- Some hexagons, from the Stanford D School

- Our very own Digital Transformation Agency’s service standard – this is how the federal government thinks we should do it

- A circle version of the Stanford one

- This squiggly thing ???

- Sometimes they get super-detailed, and maybe just a bit confusing

- I actually like squiggly the best

I’m showing you all these just to indicate that there is no specific consensus on what ‘design thinking’ means – which kinda makes it hard to talk about. There is, though, there is a general consensus.

I would argue actually that it doesn’t really matter how you map it out. What matters is what these models share.

What they share, is that they all start with problem definition (through various kinds of research and engagement with communities),

And they all involve iterative learning by prototyping and testing multiple solutions to a problem until you arrive at one that is likely to work.

- All attempt to articulate a process, or a set of principles, for problem framing and problem solving

- All start with the need for discovery and definition before building things

- All involve testing of assumptions and iterative learning while building solutions

- All are human-centred, focusing on addressing people’s needs

The ‘design’ in ‘design thinking’ is about the process of rapid discovery and evaluation of problems, and solutions to those problems.

It’s about diverging and converging. Diverging and converging. —

I said I like squiggly the best – what the squiggly line represents is the clarity that design thinking gives you – the clarity to know you are on the right track. This develops over time, over the course of a project.

This is a lot of information up front in a talk like this – I just want to say here – I’m not planning on leaving you today with a full understanding of everything there is to know about design thinking. There’s not enough time for that. Instead I hope to show that the process has value for the work you do, and hopefully spark your interest so that you look into it a bit more. I needed to do this bit first to show that there is a process.

The easiest way for me to explain what this looks like in practice will be to talk you.

I’m going to use examples from Paper Giant’s own consultancy practice – not because they are the ‘best possible archetypes of design thinking’, but because I know them the best, and so will be able to elaborate on them the most if you have any questions later.

Also, because Rebecca asked me to bring along some case studies. She said ‘bring lots’.

I’ve actually only chosen 2, which I know is not lots – I’d rather talk in more detail to demonstrate the deep value that design thinking brings. Feel free to bail me up afterwards and I can give you loads more examples – it took me a while to settle on these two.

I was even going to include a project with a technology health provider in Toowoomba last year, but it felt like tokenism from the “Melbourne guy” and I know that you’re all smarter than that.

I’m going to talk in detail about 2 projects:

- Work we did for the Federal Government looking at the variety of experiences for people dealing with the death of a loved one

- Work we completed for the community legal sector in Victoria addressing the needs of people caught up in the fines system.

I’ve chosen these projects because ways they illustrate different aspects of design thinking and social innovation working together.

Project one – I’m gonna start with some stories.

A quick warning – this project was about death, so some of the following might be emotionally triggering for some people. I apologise in advance, and feel free to either leave, or talk to me afterwards if you’d like to be directed to some support.

This is Marina

When Marina’s father died, he left his entire estate to her documented in his will. What he didn’t do though, is he didn’t tell his long-term girlfriend his wishes, and when he died, she contested the will. The legal proceedings and probate processes that followed led to years of compounded stress for Marina.

As a result of this terrible experience with her dad, she developed her own “insurance” against family squabbles in the future – she arranged to video her mother in the presence of a lawyer, so her mother’s wishes were documented not just on paper, but also in a personal way that would be much harder to challenge in court.

This is Qi

Qi lives in Australia, and one day, when his elderly mother Jing was visiting from China, she died, unexpectedly, from lung fibrosis.

Qi had no extended family support, and had to navigate laws and customs from both countries. Their cultural practices meant that his mother needed to be cremated with many items of clothing and personal effects, which was particularly hard to arrange in Australia because of the laws around cremation.

Qi’s cultural practice also meant that his mother’s ashes could not be kept in any place that would be considered domestic’, which included Qi’s car – he actually had to transport her ashes by Uber, and had to rent a hotel room to store them until he could sort out the complex documentation, translating from Chinese to English and back again from the various consular departments, so that he could get permission to export ashes from Australia and import them to China.

As you can imagine, this was a huge, stressful, and upsetting administrative task on the occasion of his mum’s unexpected death.

These are two stories are from a project last year, when we were asked by the Federal Government to report on the experience Australians had dealing with the death of a loved one.

The purpose of this work was to help improve government services across a really difficult and traumatic experience. They had a hunch they weren’t doing as well as they could. They didn’t know why.

We collected over 40 of these kinds of stories, touching on interactions with legal and financial planning services, many government departments – federal and state, funeral, bereavement and counselling services, hospitals, and more.

We talked to professionals in this space – nurses, funeral directors, police officers.

We correlated these experiences with other research and ABS data.

We also developed a detailed understanding on what it means to have a ‘good death’ or a ‘bad death’ in Australia, and where government services were failing individually, failing to interact with each other, or failing to provide any support at all when in fact they could easily be doing so.

We were able to report on the variety of experience, and mapped the experience to share back to the government. The outcomes of this work pointed to multiple opportunities for the federal government to act – through different service and product interventions – to improve this experience for all Australians.

The report from this project is publically available – please let me know if you’d like a copy.

The reason I’ve chosen to speak about this project is that it sits here in terms of design thinking – it’s about mapping the problem space so that new and innovative solutions can be developed.

And this is a key difference between design thinking to some other change approaches – many projects start with a preconceived or proposed solution to a ‘known’ problem, rather than truly understanding the problem first.

One aspect of how design thinking can work with social innovation, is that it helps you frame new questions and consider solutions to problems that you would never have considered otherwise.

Good design begins with research into real experiences of individuals, not demographic and market-segment data.

The key factor here is to acknowledge that you don’t necessarily know:

- Why services fail

- Where opportunities for improvement might lie

- Or what questions to ask in the first place

Design thinking – especially, what we call design research, tells you things about context that you never would find otherwise.

Think about the relationship between, say, cultural norms, cremation services, consular services, laws around transport of human remains, translation services, private enterprise (uber and hotels), and Qi’s experience in my story earlier.

When you hear a story like Marina’s, framing a question of ‘how might we help people better share their wishes prior to death’ becomes possible, and so does thinking through the social and potential economic value of providing solutions to that problem.

One more short example – When you hear a story, firsthand, about a woman being unceremoniously handed, by a police officer, the noose that her son used to commit suicide, you truly see the value in investigating ‘sensitivity training’ for emergency services as a way to improve services.

Start with research that ‘opens up’ in this way – shows you how problems play out in the real world, and affect real people – so that you can design solutions that meet their real needs.

Design approaches like this – what we call ‘human centred’ approaches – are about involving the community in a process of solving social problems, and thinking of people’s needs first. In order to innovate in a social space you need to understand the social space first.

This second project is one we conducted for the community legal sector in Victoria last year. Not a government project (though it touches on areas of government policy in many ways).

The reason I’ve chosen to talk about this project is Design thinking helps us consider social problems in strategic ways, so that we can have greater impact with limited resources than on just the tightly defined ‘issue’ in our departmental or organisational silo.

Design thinking also gives us safe ways of testing product, service and policy interventions through a robust process that’s more likely to lead to uptake and successful rollout of your innovation.

So – this project:

Fines and infringements, and the processing and handling of fines and infringements is a major issue in Victoria and a major source of pressure on the community legal sector in particular – which is a draw on public sector funding. Taxpayer money.

Here’s another story.

A 50 year old man, let’s call him Nick, a client of a legal and financial counselling service we were working with, had so many infringements that he would lose his house if he paid them. He would also lose his house if he ended up in Jail because he didn’t pay them. This man was recovering from a serious drug addiction – he’d got himself out of that situation, but the risk was that he could pay his fines, be made homeless, and, in his words, would ‘end up dead’ because he would just go back to abusing drugs again. This is his file.

The financial counselor we spoke to managed to get him onto a payment plan, got arranged for him to take on some borders to pay the mortgage. She counselled him to find work to keep going till he was 55 so he could access his super, and arranged a special circumstances provision on account of his drug addiction so that he could get some of his super insurance.

As you can imagine this took a long time to sort out – multiple consults, digging around for documentation and medical records, administration.

People in rehab often have serious financial difficulty as a result of their addiction, and have sometimes collected 10 thousand dollars or more in fines. Extreme cases, like Nick’s, can be 80 thousand dollars. People get to the point where they are going to lose their house or go to jail.

This is a social problem. The government is not getting generating revenue from these people – it often costs more to recover the fines than the value of them.

It causes undue stress on the community and pain to real people in need.

How might we address issues for a large group of clients like this with limited funding resources for staff?

The obvious things we might look for are ways to streamline the process – collecting info, managing intake, better counselling? Maybe some kind of self-service or automation? AI and machine learning maybe?

A key factor in a design thinking approach is test your assumptions. The assumption here – and it’s a common one – is that we, as a society, should always direct resources towards those most in need.

What happens when you look at this problem in another way?

Looking at the systemic level – the community legal sector is almost entirely funded by the government – through operational funding, and grant funding for specific projects. It’s taxpayer money.

A lot of this money is actually ‘wasted’ – dealing, not with clients in dire need like Nick, but with a ‘middle’ cohort of people that really should not be any pressure on the sector at all. These are people who have what we call ‘high legal capability’ – they could help themselves if they had the means and the information to do so. Those means are hard to find, and so they call Legal Aid or a community legal centre and take up valuable time that could be spent dealing with more urgent matters. A lot of this pressure is fines related. We’re talking 1 or 2 parking fines or a public transport fine, not 80 thousand dollars like Nick.

The reason dealing with clients like Nick is is a problem, is that there is not enough time to work with them, not that the system for helping them fails – Remember – Nick’s story was a success story.

Design thinking helps us ask questions like: ‘how might we take pressure off the system in the first place so we can help people like Nick better?’

And what is putting pressure on the system? It’s the people with high legal capability. This is an example of what we call ‘failure demand’ – a lot of the demand on the sector, and on other sectors, obviously, is due to failure to meet the needs of the community in the first place, and that leads them to come back for help. In all industries, the focus should be on ‘value demand’ not ‘failure demand’ – resources should be directed to where you can provide the most value, first time, not respond to failure. You need to stop the failure in the first place.

So what did ‘stop the failure’ mean in this case?

It meant designing and building a resource specifically targeted at the cohort that are not the ‘most in need’, but instead the most capable pressure on the system.

That’s what we did. FineFixer is a simple, step-by-step process to help those with the capability deal with fines in a timely manner, and those without the capability to be directed to the correct help the first time around.

Where ‘design thinking’ got us in this case was to a “divergent solution” – rather than take the standard approach of spend limited resources on those most in need – business as usual, not working – we found that we could spend some resources on those in less need, to free up resources elsewhere.

And it gave us a strategic way to anonymously collect more data on the people who are in need, so we can advocate for policy change in the midst of Victoria’s fines reform.

A definition of ‘policy’ that I like is “Policy” is how organisations arrange their resources to express operational and strategic goals. You choose resource allocation, that’s policy.

The key learning here is that you don’t have to target your direct ‘audience’ or ‘customers’ to have the social benefits that your policy is trying to achieve – you can, through strategic social innovation, direct your resources in clever ways that free you to provide better service to the community overall.

I’d note too that this was not a ‘technology driven’ project – often innovation is seen as synonymous with technology and I just think this is flat out wrong – yes, we built a technology solution. But the focus was always on the people and the problem. The technology is one component in a system of people and processes and the law and policy.

You might well ask… how do we know that this new component of a complex system will even work? In design thinking – you test it. Extensively, multiple times, and early using prototypes – as it is developed. You test things with the community of users who will actually use your innovation. And you learn from that experience and iterate on it, and improve it, and you test it again, until you have something that has a real chance of success.

This process of designing + testing + iterating is really the core of what design thinking is about for me. It’s not about ‘thinking super hard in a designerly way and then coming up with the perfect solution.’ That’s impossible, because the systems of people and technology and infrastructure and policy in which we operating are just too complex to understand in that way.

Design thinking helps you move deliberately towards social innovations in ways that are, in fact, way safer than just releasing a big-bang, expensive solution to a problem that you’ve identified. If forces you to analyse the problem space, assess a range of options, test those in the real world, and adopt sustainable solutions that meet real needs.

They’re my two examples for today. I hope they’ve been interesting for you to hear about.

The point of doing this kind of work of course, is to arrive at solutions to social problems.

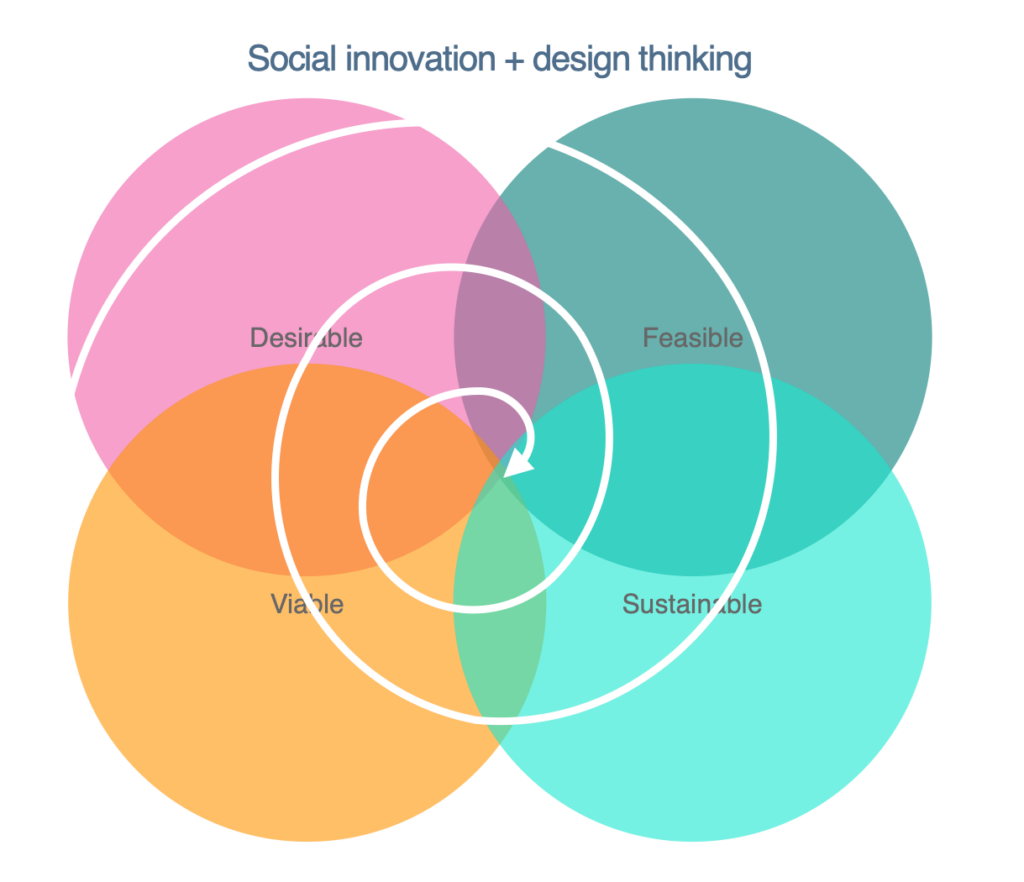

What we want is solutions that are desirable, feasible and viable:

- Desirable – people want it

- Feasible – it’s possible to make it in the current environment

- Viable – we can make it with the resources we have

When working in social innovation we like to add one more to this equation: Sustainable – we can maintain it and it’s not an undue drain on resources (internal or external).

We want to innovate to make better use our limited resources to make a better society in the face of these problems, because ‘business as usual’ approaches to solving problems don’t seem to be working – the status quo, is failing us.

Design thinking might be effective way to define our problems, develop innovations, and work towards desirable, feasible, viable and sustainable futures

Sounds pretty good, right?

There’s a sweet spot that you want to hit. Design thinking helps you converge on that sweet spot.

Now – as anyone that’s currently trying to bring this approach to government – myself included – you know that applying this stuff is hard.

Systems, organisations, governments, societies – are complex.

In order to use design thinking effectively, to do that convergence on the ‘right’ solution, you first need to acknowledge that you don’t know the answers.

or sometimes, even the right questions.

You might not know the answers, or the right questions.

This is hard to do, especially in careers where you are expected to be ‘experts’ in your subject matter.

I’m lucky that I’m a researcher – the one thing I know is that I don’t know much at all about anything – but I know how to find out, and design thinking helps me do that in a systematic way.

When it comes to implementing innovations – the design process is really good at discovering where and how things are likely to fail, well before you actually fail.

It’s less risky than other forms of policy and service development, because if you test assumptions early and often, and you engage affected communities through the process, not just in ‘consultation’ as a box checking exercise, but truly engage them in designing solutions for the communities themselves, and it dramatically increases your chance of uptake and success.

When you apply design thinking to a problem, you discover that many other organizations play critical roles in people’s lives – you might be really good at delivering your service, but maybe the failure lies somewhere else?

Maybe it lies in information flow? Maybe the service works when there is uptake, but there is some blocker to uptake that you don’t control, but can work around?

Find out – break down those silos. Work to truly understand your context and design solutions that cross service and departmental boundaries.

You might be thinking – ‘all sounds great for your examples – death experiences and community legal problems, but how does it apply to my context?’

Ask yourself:

- Does my context involve people?

- Does it involve interactions in the world between people, systems, policy, and culture?

If the answer is yes (and if you work in government, it’s almost certainly yes), then Design Thinking is for you.

If there is one thing I’d like you to take away from my talk today its this:

Design thinking means designing for and with real people, and making decisions based on real needs

What I love about design’s human-centred approach to problem solving is the way it helps you take a broader, collaborative, and more inclusive view of who should be part of the process – it’s inclusive.

Good design is about understanding community needs and the wider context in which services will be used, or the wider context in which policy will have impact.

It’s about articulating and testing assumptions, and reaching shared understandings – of both the social problems we face, and the solutions to them that will actually work.

How can we make the world better?

More just, more fair, more equal, more sustainable?

Everyday?

Thanks very much.