Ethics in Design Research

The following is a transcript of a talk I gave at Design Research Australia, Melbourne, March 2018

My name’s Reuben Stanton. I’m the design director and a co-founder of Paper Giant.

Paper Giant is a research led design consultancy based here in Melbourne. We help organisations, governments, and not for profits understand and solve complex problems. We work across the spectrum of design projects: from discovery and problem space research, right through to service delivery, implementation and evaluation.

Today, I’m here to talk about ethics in design research.

I’ll talk about what I mean by ‘ethics in design.’ I’m going to present a framework we’ve been exploring at Paper Giant for thinking through ethical issues in design research. And I’m going to use project examples from Paper Giant’s work — not because it’s the ‘best’ or ‘most ethical’, but because that’s the work I know the best.

So… “ethics”… what even is it?

By “ethics” I mean the moral principles that govern our work — more simply ‘how to be good’. Our ethics is expressed through what we do: our effects on the world.

I’m going to bring up on screen my favourite quote about design ethics. It’s from a philosopher named Peter Paul Verbeek — there are plenty of great writers and thinkers about ethics in design, this is just one that really resonates with me:

If ethics is about the question of how to act, and designers help to shape how technologies mediate action, designing should be considered ‘ethics by other means’.

Every technological artefact that is used will mediate human actions, and every act of design therefore helps to constitute specific moral practices.

What Verbeek is saying here is that by doing design you are doing ethics.

Or more simply: Design has moral consequences, so be deliberate about your actions.

We have a responsibility for what we make and how it affects the world

To be ethical means to take a deliberate stance on how your actions play out. For example, my ethics, and those of Paper Giant, are like this:

1. Make positive social change through design

2. Help the most vulnerable in society

3. Do no harm, and help others do no harm

The point of all this is that ethics are manifestation of values in action. You choose your values, and you act. What we make as designers (and research is absolutely a form of making), encourages and enables certain kinds of action.

This framework I’m about to present is a way to help us think through exactly how our work is an expression of moral values.

It emerged from reflection on the work we, at Paper Giant, have done in the past, and the kinds of questions we’ve grappled with.

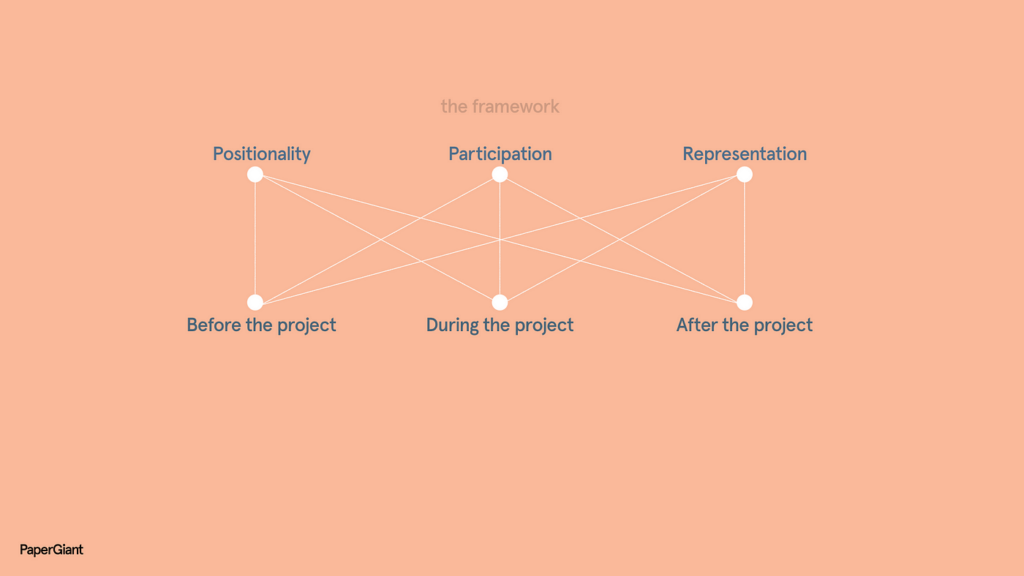

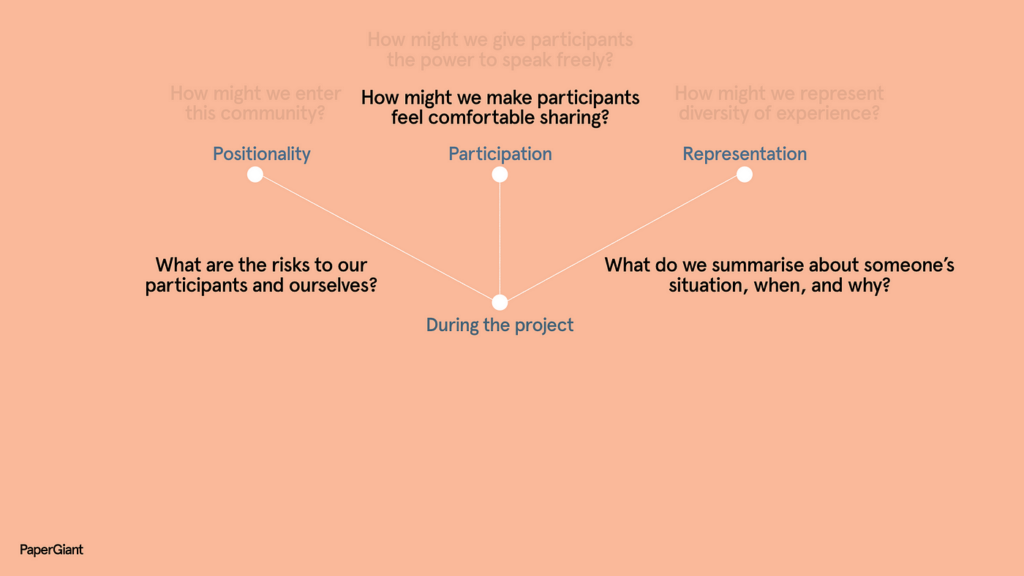

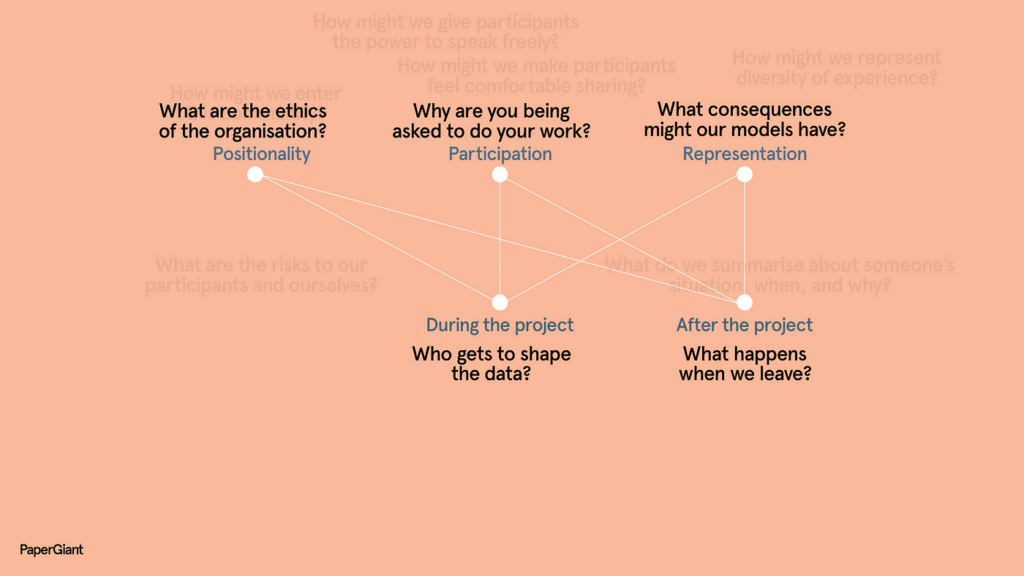

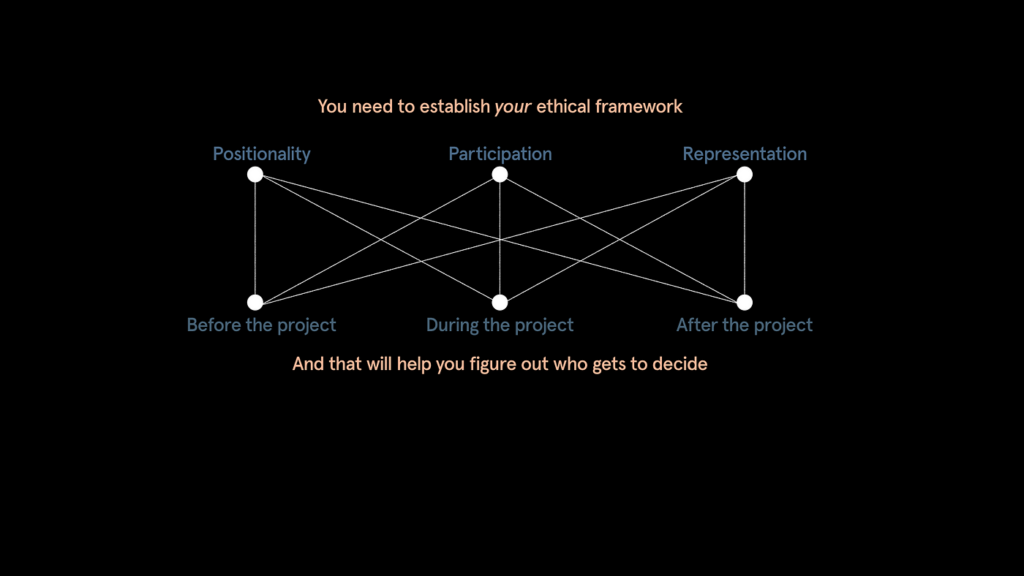

It’s pretty simple — it’s really just a list of some things to pay attention to when working. Positionality, participation, and representation:

- Positionality: who am I in relation to this work?

- Participation: who participates in this work, and in what ways?

- Representation: what gets represented, and crucially, by whom?

Below each of these are points in time. Before, during and after a project. These are pretty self explanatory. It’s when you need to pay attention. And there are relations between these elements.

It’s a framework, not a model. It helps frame questions, not answers. It helps us interrogate methods, it is not a set of methods.

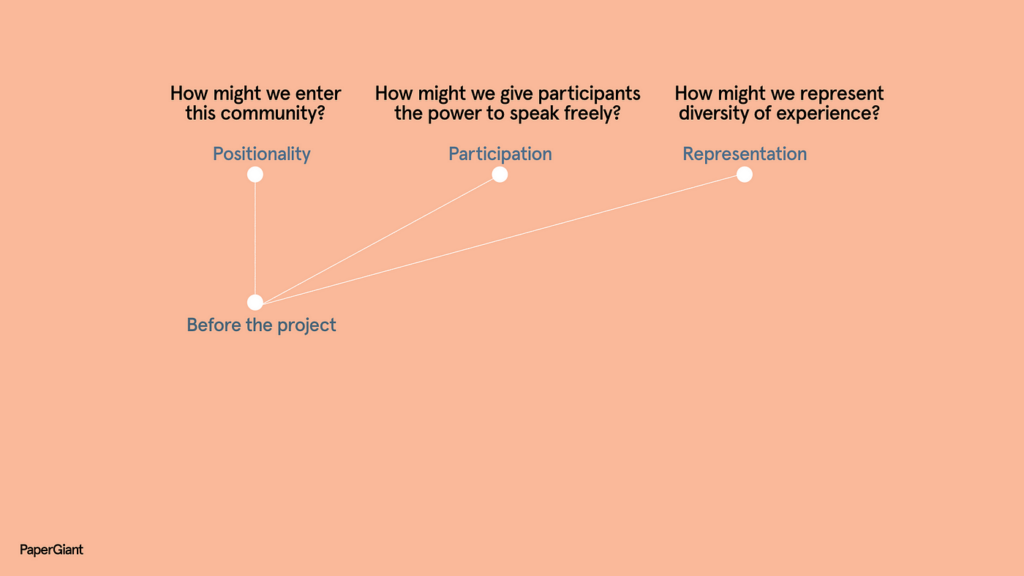

In one project a few years ago, we were tasked with conducting research into sexual health issues with refugee and migrant teenagers.

As design researchers, this was a pretty tricky context. We were working with young people, with English as a second or third language, and a pretty sensitive subject matter.

Let’s think about positionality: we, as white (or mostly white), middle class, Australian born, educated, adult researchers… maybe it’s not ok to just recruit some vulnerable young people and start asking them about their sex lives.

So what did we do?

Participation: We started with social workers who had loads of experience working directly with these communities. We gave them the opportunity to participate in the design of research methods with us, so that we could create safe spaces for participants to speak freely and openly.

Representation: We came up with a way of using comics to represent realistic, diverse scenarios that participants could talk about and to rather then talk about themselves. We designed research sessions that involved social workers as participant-researchers.

A few pre-project considerations

These were the kinds of questions we were asking before the project started:

- How might we enter this community?

- How might we give participants power to speak freely?

- How might we represent diversity of experience?

In this case — ‘do good’ meant consult with the people that know the community first, and be flexible with methodology to suit the context.

Are we ok with that?

Another example: in a project last year we were asked by the Federal Government to report on the experience Australians had dealing with the death of a loved one.

The purpose of this work was to help improve a range of government services across a really difficult and traumatic experience.

We conducted about 40 interviews with people who’d lost someone between 6 and 18 months ago, as well as professionals in this space — nurses, funeral directors, police officers. We reported on the variety of experience, and mapped the experience to report back to the government.

So — just thinking about what it was like during this research:

Some questions you might ask about your work

When you’re working with government services, you’re working in places that are rife with structural inequality — it’s not often, for example, that people from lower socioeconomic backgrounds get to talk directly to a government department about how they were let down when their friend died… how might we make sure that we don’t squander, on their behalf, that opportunity?

Here are some of the questions we were asking:

- Positionality: What are the risks to our participants and ourselves? How might we mitigate those risks?

- Participation: How can we make participants comfortable sharing with us? How can we do that safely?

- Representation: What of the diversity of experience do we summarise and aggregate? When and why might we do that and what might we lose in the process?

In this case, ‘do good’, meant always remembering that our participants were people, not resources to extract data from for our purposes. It was about focussing on building safe connections — we didn’t want to turn this into ‘lets all be amateur social workers for an hour’ — there were serious risks to our staff and our participants in just having these conversations, and we engaged experts to make sure we did this safely. We had to put supports in place to make sure no-one was harmed in the process.

Our role was to represent the diversity of experience in a sensitive way, to treat people ( including our staff) with respect and kindness. Our behaviour as researchers needed to be a supportive one, not an extractive one.

Are we ok with that?

I find thinking about client relationships really interesting in an ethical context. In this next project, a health insurer asked us to conduct some research work with parents of Autistic children — it was NDIS related work.

We interviewed parents, we made journey maps, we developed product concepts and pitches, we ran co-design sessions with stakeholders in the business.

Now, spoiler alert… the client already had a solution in mind.

They’d already started funding and building it. They were only really looking for data that supported their solution. I see some nods of recognition… has that ever happened to anyone here?

Thinking about during, and after the project — we aimed to report accurately, and in ways that we believed would genuinely help the people we talked to. The client had a predetermined business plan, that probably, based on our research, wouldn’t meet their needs.

Sometimes research and business goals are in conflict – so pay attention!

A bit of a mantra at Paper Giant is that there is no such thing as objective data — data is shaped:

- By recruitment methods

- By the positionality of the researchers

- By the questions you ask when collecting data

- By the questions you ask of the data as you interpret it (this goes for quantitative data too!)

- By questions others are asking you to ask

- By the ways that data gets represented or presented back to a client

Think about the choices you make day-to-day within organisations. What do you know about their broader strategic goals? What are you looking for in the data and why? Who is asking you to look in that way?

How is your work being shaped by the political and ethical framework of your client? When you leave — what design are you enabling? Do the likely outcomes align with values you support? Whose lives are you impacting, and how?

Your work will be used, and it’s largely out of your control. What can you do now, to prevent, or mitigate, misuse? Is it good enough to help an organisation do “slightly less-worse” than they might have done without you there?

Are you ok with that?

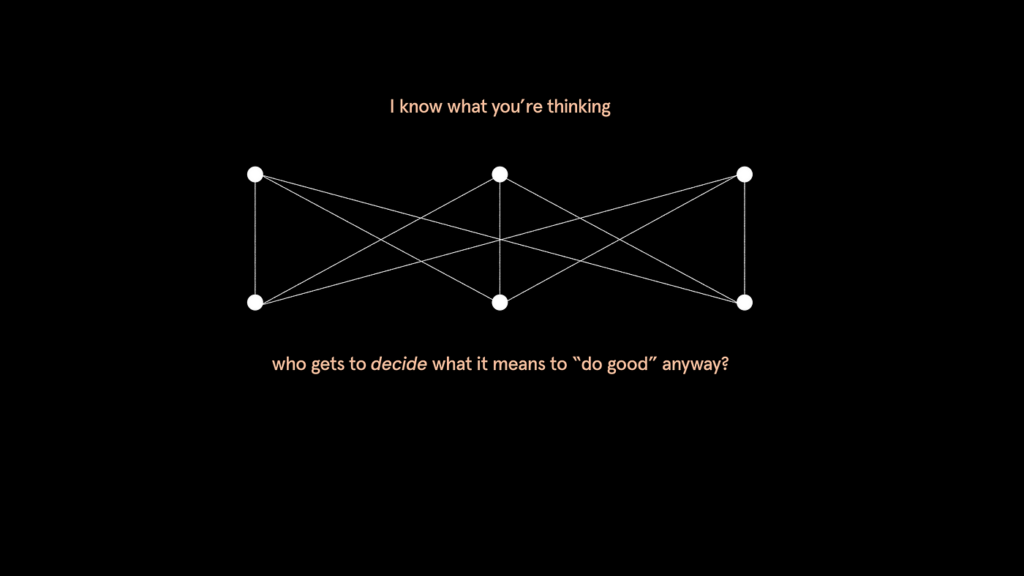

In any case, what right do I have, a hipster director of a small design company, hanging out in Melbourne in my tight jeans, and designer shirt and expensive boots, drinking coffee, to tell anyone what ‘good’ looks like? What gives any of us, as researchers, that right?

Good question!

Ethics is expressed through action. So we need to ask, as designers & researchers: “what should we do, or not do, in a particular context?” Because to not act is also a choice that we can make.

Last project example. This one is a bit different from the others.

We conducted research in a partnership with RMIT University into contemporary representations of Aboriginality amongst the Wiradjuri people in New South Wales.

We had loads of ethical questions we were grappling with. What right, as outsiders, did we even have to enter the community? Collect data? Represent anything back?

I think we didn’t have that right. And, as a team, we ended up deciding that the best way to conduct this research was to give people, in a community that we weren’t part of, a platform to speak to each other, and not to us.

As part of this project we built a digital platform for recording conversations in the community about relationships to country, language, indigeneity. And we built tools to help the community own, manage and interpret that data as they saw fit. Our role was not researching and not reporting.

Sometimes, to be a good design researcher means to acknowledge your limitations, and to give away as much of your power as possible — to let others, with less privilege than you, make their own determinations as to what ‘good research’ even means.

Are we ok with that?

So back to that question — who gets to decide?

Designers and design researchers are seriously privileged — we frame questions, we shape data, we interpret for people and organisations and government, we influence and implement products and services and systems and policy and futures.

It’s not hyperbole to say that the insights we generate, the models of the world we create, determine courses of action for whole swathes of society.

It’s imperative, as a designer, or researcher, or both, that you to establish your own ethical guidelines — I’ve touched on a few of ours at Paper Giant — you might have others. Decide what you are ok with. Find ways to lend your privilege to those with less power. Find ways to let others challenge your moral framework and your understanding of what good even means for communities.

Design has moral consequences, so be deliberate about your actions, by continually interrogating your practice

I’ve talked about this in terms of design-research today, but I hope you can see how this applies to any and all parts of a design process.

Design researchers are really lucky! We work in contexts where we get to choose — what questions get asked, what data gets collected, what gets shared, how findings are represented. Every single one of these choices has ethical implications.

This might seem daunting, but I actually find this exciting — it means we get to choose to do good, all the time! Not many jobs give you that opportunity.

The most important thing is to ask yourself and your colleagues questions, and, pay attention to your answers.

Do your actions reflect your values?

How will your actions help the ‘good’ version of the future come into being?

And are we ok with that?